A Pocketbook of Psychological Aid

LVIV “BONA” Publishing House 2023“A Pocketbook of Psychological Aid” was written for psychologists, social workers, volunteers, and assisting professionals, involved in the work with people displaced due to the war in Ukraine. This project is being implemented in cooperation with the German Association of Psychosocial Centres for Refugees and Victims of Torture (BAfF) with financial support from the Federal Foreign Ministry of Germany.

The authors of the materials, collected in this book, are psychologists and psychotherapists of the Charitable Organization Charitable Foundation “ROKADA”.

About the textbook

From the standpoint of evolution, it is normal for people to live in permanent danger, yet we are living in conditions of total uncertainty. War destroys the values of life and culture, which have been built over the course of centuries. It is killing not only people but also the economy, infrastructure, and culture. War is a state of mind when, at any minute, you are willing to sacrifice your own life to protect the values you live for. This is a state of war. Many people have already been and will conscientiously be in it from now on. Adaptation to stress is built gradually; it is important to help ourselves cope with this pressure, increased anxiety, and other unknown manifestations of our mind as responses to different events in our life.

We often ask ourselves: how can we reduce anxiety and preserve our psychological state during the war? How do we find strength and resources within ourselves to support both ourselves and others? How do we start a dialogue with ourselves and talk about our feelings in this complicated period? Understanding the ways to practice psychological self-aid during the war is a crucial element in ensuring psychological resilience and maintaining balance.

This pocketbook was designed to provide and use information about mental health and psychosocial problems in conditions of humanitarian and mental crises. Each section contains the main information about a specific issue of mental health, features and symptoms, reasons, and recommended ways to search for assistance. This textbook is aimed at helping practicians provide psychological aid in a better way, letting specialists understand their state through a “person-to-person” interaction type and raising the awareness of people in need of assistance about the relevance of searching for it. In addition, this information can be used for psychoeducation and raising awareness of people who go on living in a state of war. Psychoeducation allows for the acknowledgement of the fact that a person, living in a state of war is vulnerable and can have several symptoms, which are normal reactions to an abnormal situation. It is difficult to live with these symptoms, but they have developed as a defence reaction for survival. If one understands them, they will be easier to manage.

Therefore, the initiative of creating a textbook in a convenient format is important, and we hope that it will become a resource of knowledge and skills, a hint for practicians and support for other readers, which is critical in this complicated period of our trial...

The road to healing is long but we are already on it...

PSYCHOLOGICAL FIRST AID (PFA)

There are various tragic events in our world: wars, natural disasters, catastrophes, fires, interpersonal violence, etc. They may affect specific individuals, families, or entire communities. People may lose their homes or their loved ones, be separated from their families and communities, or witness violence, destruction, and death. Everyone has their own strengths and abilities, which help them overcome hardships in life. However, in an emergency, people are especially vulnerable and need additional knowledge of the basic issues of psychological first aid (PFA).

What is PFA?

The main feature of psychological first aid is its simplicity.

Therefore, psychological first aid is a combination of the acts of general human support and practical psychological assistance to people affected by significant stress factors.

Its provision does not require any special professional training; it is enough to have the knowledge obtained from this textbook and a natural ability to express compassion. PFA comprises the following elements:

– non-intrusive provision of practical assistance and support;

– evaluation of needs and problems;

– assistance in meeting basic needs (e.g., food, water, information);

– listening to people without forcing them to speak;

– provision of consolation and relief to people;

– assistance with obtaining information, addressing the services and structures of social support;

– protection of people from further harm.

While providing psychological first aid, it is necessary:

- to find a quiet place for a conversation with no distractions;

- to respect the confidentiality and refrain from disclosing the obtained personal data;

- to be close to a person but keep the required distance, considering his/her age, gender, and culture (if a hug is needed, you have to ask for permission first);

- to show your interest, e.g., by slightly nodding or uttering short affirmative replies;

- to be calm and patient;

- to provide actual information, to speak honestly about your knowledge, “I don’t know, but I will try to find it out for you”;

- to give the information in understandable terms, in plain words;

- to express commiseration with people who tell you about their feelings, losses, or important events (the loss of a house, the death of a close person, etc.);

- to give a person a chance to keep silent for a while.

Who needs PFA?

PFA is intended for people in distress due to a recent complicated crisis-related event. You can provide this aid to both adults and children. Yet, not every crisis survivor needs PFA or wants to receive it. Do not impose your assistance on those who do not wish to receive it; instead, be available to those who might need your support.

Persons in need of more professional emergency assistance:

– persons with serious life-threatening traumas who will need emergency medical assistance;

– persons in such distress that they are unable to take care of themselves or their children;

– persons who may inflict self-harm;

– persons who may bring harm to others.

The foundation of responsible provision of aid lies in four ideas:

1. Respect for human safety, dignity, and rights

Taking upon yourself a responsibility to help people when they suffer from a stressful event, it is crucial to act with respect for the safety, dignity, and rights of the people you are trying to help.

RESPECT FOR SAFETY — avoid situations when people may suffer additionally due to your actions. It is important to guarantee safety and protection from physical and psychological harm for the adults and children you are trying to help.

RESPECT FOR DIGNITY — treat people with respect, considering life values as well as their cultural, social, and religious norms.

RESPECT FOR THE RIGHTS — ensure equal provision of aid to people, without any manifestation of discrimination. Assist people in defending their rights and accessing the available support. While helping, you should be governed only by the interests of a victim (see Fig. 1).

2. Adaptation of your own actions to the cultural traditions of the population that suffered from a crisis. There are people with different cultural traditions, inherent reactions/expectations regarding treatment, which we may not know due to intercultural differences.

|

You should |

You should not |

|

- Be honest and reliable. - Respect the right of a person to make his/her own decisions. - Realize and refuse from your own prejudices and stereotypes. - Explain in simple words to people that if they refuse assistance now, they can still receive it in the future. - Respect privacy and ensure proper confidentiality of people’s stories. - Behave properly, taking into consideration the specificities of a person's culture, age, and gender. |

- Abuse your position as an aid provider. - Ask people for money or services in exchange for the aid. - Give empty promises and wrong information. - Exaggerate your abilities. - Impose your assistance; be obtrusive and too persistent. - Force people to tell their stories. - Retell a person’s story to others. - Condemn a person for actions or feelings. |

Fig. 1. Behavioural patterns

3. Being informed about other types of response to an emergency. While providing the aid in the crisis-related situation, if possible:

- act according to the instructions of the relevant state authorities who manage the program of crisis response;

- find out which measures of responding to an emergency are being taken and which resources are available for people (if there are such resources);

- do not hinder search-and-rescue operations or the work of medical workers of the emergency teams;

- realize your functions and their limitations.

4. Self-care. The responsible provision of the aid also envisages taking care of your own health and well-being. As an assistance provider, you may be negatively affected by your experience of a crisis; besides, you or your family may be immediate victims of these events. It is important to pay special attention to your own well-being and be confident that you are capable of helping others both physically and emotionally. Take care of yourself to have the possibility to take care of others.

Efficient communication with people in distress

The manner of your communication with a person in distress is crucial. People who have just experienced a crisis event may be subdued, anxious, or confused. Some people may blame themselves for what has happened. Keeping calm and expressing your understanding, you help people in distress feel safer and protected and see that they are understood, respected, and taken care of properly.

Some people who have just suffered from a stressful situation may want to tell what has happened to them. To listen to someone’s story is a great support in itself. However, it is important not to force a person to talk about a traumatic experience. Some people may not want to speak about what has happened or about their personal circumstances. However, they may appreciate your staying with them in silence, assuring them that you are close and that they can talk to you if they choose to, or your offering them practical assistance, like some food or a glass of water. Do not talk much. A possibility to keep silent for some time may create a necessary space for a person and encourage him/her to share his/her experiences with you if he/she chooses to. To communicate effectively, mind what you say and pay attention to your body language, including mimics, visual contact, and gestures. Below are recommendations on what you should and should not say and do. The most important thing is to be yourself, act naturally, and be sincere, offering assistance and care. Crises are often exacerbated by emerging chaos, when one has to act in an emergency. If possible, try to get accurate information before going to the place of a crisis event. Keep visual contact with a person during the conversation.

Table 1. The comparative table of actions and phrases which should/should not be done/expressed

|

WHAT YOU SHOULD do and say |

WHAT YOU SHOULD NOT do or say |

|

Find a quiet place for a conversation with no distractions |

Force people to tell what has happened to them |

|

Respect the confidentiality and, if possible, do not disclose the obtained personal data of a person |

Interrupt, hurry an interlocutor (e.g., you should not look at your watch or speak too fast) |

|

Be close to people but keep a required distance considering their age, gender, and culture |

Touch a person if you are not sure whether it is acceptable in his/her cultural environment |

|

Show that you are listening to the interlocutor attentively, e.g., by nodding or saying short affirmative replies |

Evaluate the person’s actions |

Continuation of Table 1.

|

WHAT YOU SHOULD do and say |

WHAT YOU SHOULD NOT do or say |

|

Be calm and patient |

Say, “You should not feel that” or “You should be glad to have survived” |

|

Provide actual information if it is available. Tell honestly what you know and what you don’t know, “I don’t know, but I will try to find it out for you.” |

Make up something you don’t know |

|

Provide information in simple words for easy understanding |

Use special terms |

|

Express commiseration when people talk about their feelings, a loss they have suffered, or important events (the loss of a house, the death of a close person, etc.): “What a disaster! I understand how difficult it must be for you.” |

Give promises or assurances, in the implementation of which you are not sure |

Continuation of Table 1.

|

WHAT YOU SHOULD do and say |

WHAT YOU SHOULD NOT do or say |

|

Highlight the attempts of a person aimed at his/her finding a way out of a difficult situation on his/her own |

Share with your interlocutor the stories you heard from others |

|

Give a person a chance to keep silent if needed |

Talk about your personal hardships |

|

Think and act as if you are obliged to solve all the person’s problems for him/her |

|

|

Deprive a person of any confidence in his/her own strength and ability to take care of himself/herself |

|

|

Talk about people using negative epithets (e.g., call them “crazy”) |

Operational rules of PFA: look, listen, link

The main three operational rules of providing psychological first aid are as follows: look, listen, and link. These rules help evaluate the crisis situation, ensure your own safety at the place of the event, find an approach to the internally displaced persons, understand their needs, and direct them to the place where they can get practical assistance and information.

LOOK: it is essential to check the security measures to find out whether there are people in actual need for basic necessities of life, and to check whether there are people in high distress.

LISTEN: it is important to talk to people who might need assistance, to find out what exactly they need and what worries them, to listen to them and to try to calm them down.

LINK: people who have experienced a traumatic event often feel unprotected, cut off from the world, and helpless. Their routine life is ruined; they do not receive their usual support any longer or experience sudden stressful conditions. Directing people to places where they will be provided with practical assistance is one of the primary purposes of PFA. PFA is usually a single intervention, and you can be close to a person only for a short time. For further recovery of this person, you should encourage him/her to apply their own skills for coping with a life situation. Help people get over it on their own and restore their control over the situation.

TERMINATION OF AID PROVISION

The determination of when and how the aid provision is terminated depends on the crisis conditions, the role and functions of the aid provider, and the needs of the people requiring assistance. You should rely on your evaluation of the situation, the needs of the people in your care, and your own needs. If necessary, you should tell people that you are ending your assistance, that someone else will help them from now on, and make them acquainted with the new caregiver. If you link people to other services, you should explain what they can expect and ensure they have the information required to maintain further communication. Regardless of the experience of your communication with a person, it is important to bid your farewell on a positive note, wishing him/her well.

Thus, while addressing people who may need support:

- address them with respect and in accordance with their culture;

- introduce yourself, tell your name and organization;

- ask them whether they need any assistance and which assistance they need;

- if possible, find a safe and quiet place for a conversation;

- create simple, comfortable conditions (e.g., give them some water);

- try to ensure the victim’s safety: take a person out of the place of immediate danger, if it can be done without any risks; try to protect a person from intrusive attention, defending his/her right to privacy and dignity; if a person is depressed, try not to leave him/her alone;

- listen to people and try to calm them down;

- be close;

- do not force people to talk about their traumatic experience;

- listen carefully if they choose to tell what has happened;

- if a person has experienced severe stress, try to calm him/her down and make sure that he/she does not stay alone;

- keep visual contact with a person during the conversation.

The material was elaborated and formed by: Nadiia Perius, Olha Yurtsyniuk (Chernivtsi)

References:

1 Psychological First Aid: A textbook for local specialists. – Kyiv: Univ. Publishing House “PULSARY”, 2017. — 64 p., il. ISBN 97896179615907897 [In Ukrainian]

- Methodological recommendations on providing psychological first aid to families with children and children who are / have been in the active combat zone / Prepared within the framework of the Project “Supporting the Reform of the Social Sector in Ukraine”, implemented by the United Nations Development Program in Ukraine. Thoughts, under the general editorship of O.L. Ivanova, compilers: Dr. Sci. (Medicine) I.Ya. Pinchuk, Dr. Sci. (Medicine) Prof. O.O. Khaustova, Ph.D. (Psychology) N.M. Stepanova, A.V. Chaika, A.O. Pinchuk. URL: https://dszn-zoda.gov.ua/node/495.

- Link to the electronic resource: https://dszn-zoda. gov.ua/node/495

Feeling of guilt

What is the feeling of guilt?

The feeling of guilt is a deep psychological state that is inherent to a person after doing something morally wrong, doubtful, or, on the contrary, not doing anything when, in the person’s opinion, something should have been done.

The feeling of guilt is a specific emotional experience which a person has when he/she believes or realizes that he/she has violated his/her own standards of behaviour or conventional moral norms and must bear relevant responsibility for this transgression [4]. This emotion is complicated and multi-faceted.

The feeling of guilt usually appears when a person conscientiously breaks standard social or personal moral norms. It may be a result of failing to fulfil one’s duty properly, a wrong action, or merely being involved in the events, which contradict one’s personal values. A relevant aspect in the feeling of guilt is the presence of conscience and responsibility for one’s actions. It is closely related to the notion of debt, duty, remorse, and shame.

The emotional dimension of the feeling of guilt is manifested in a wide spectrum, from elementary discomfort to deep suffering. It is usually accompanied by an inner dialogue in which a person analyses his/her own actions and their consequences. This inner conflict may cause anxiety, sadness, and sometimes depression. It is important to remember that the response to the feeling of guilt is individual, and each person may overcome this emotion in his/her own way [7].

The feeling of guilt is also closely connected to the attempts to compensate for the mistake which has been made. A person may try to rectify his/her own actions, apologize to the ones he/she has offended, or take responsibility for the consequences of his/her actions. This rectification process may be both internal, including self-analysis and self-management, and external, for instance, an apology to others and the work on improving one’s own character.

It should be noted that the feeling of guilt may appear not only due to actual actions but also due to a failure to act or the absence of support. For instance, the realization of the fact that you could have helped someone in their moment of need and didn’t do it may also give rise to the feeling of guilt. When we refuse to do good, fail to help those in need, or ignore moral principles, the internal conflict may become the foundation for the feeling of guilt to appear, which stimulates us to reconsider our actions and rectify the situation.

An important aspect in the understanding of the feeling of guilt is its social nature. This feeling may affect the interaction of a person with people around him/her and define his/her moral status in the group or society. It is determined by the way other people react to the manifestation of guilt and the desire to rectify the mistakes [5].

The feeling of guilt is a relevant aspect of our emotional sphere; it appears when we realize moral wrongness or non-compliance of our actions with the established norms and values. It is a complex emotion, including not only the realization of what has been done but also the desire to rectify the mistake or change one’s behaviour.

It is necessary to differentiate between the feeling of guilt and other emotions, such as shame. The ability to distinguish and work with the feeling of guilt is an important part of the emotional and social competence of each person.

One of the main functions of the feeling of guilt is to regulate social interactions and maintain harmony in the community. It acts as a unique internal mechanism aimed at supporting moral standards and meeting the requirements of the social environment. The feeling of guilt appears when we realize that our actions may harm others or violate conventional norms.

In most cases, the feeling of guilt pushes us toward self-reflection and internal evaluation. Sometimes, we ask ourselves why we have done this or that, and whether our actions were ethically appropriate. This internal discussion may be difficult and discordant with our own moral standards and responsibility for our actions.

The feeling of guilt is also related to the development of empathy. When we realize our own fault, we can understand the feelings of other people and their vulnerability better. It contributes to the creation of an environment favourable for the development of social skills and mutual understanding [3].

Noteworthy is the fact that the feeling of guilt may be disproportional or restrain a personality too much. People may experience great pressure from their inner criticism, which may lead to stress and deterioration of their mental state. It is important to learn how to accept the feeling of guilt without transforming it into an unsubstantiated self-accusation but use it as a stimulus for personal growth and improvement of relations with others.

The feeling of guilt may be related to cultural or religious values. In some cultures, it will have a greater effect on behaviour or interaction with others because they decide what is morally acceptable or unacceptable. In general, the feeling of guilt is a complicated but relevant aspect of our emotional life, which requires attention, self-reflection, and interaction with others to find an efficient solution and improve our moral standards.

Guilt is a complicated feeling, containing two other emotions: anger with oneself and fear of punishment. Thus, I am offering you a lifehack: when you feel something like guilt, ask yourself,

-

- “What for am I angry with myself in this situation? Where could I be wrong?”

- “What for am I afraid to be punished? How can I be punished in this situation?”

When you answer these questions, your attitude toward the situation that caused this feeling usually changes...

How does one discern guilt?

A feeling of guilt is a complex emotion affecting the person’s mental state and behaviour. There are several “symptoms” or manifestations of the feeling of guilt that can indicate its presence:

Sensitivity to consequences of any action

A person with a feeling of guilt may be very sensitive to the consequences of his/her actions. He/she is worried about how his/her actions affect others and may experience inner pressure related to the attitude of other people toward his/her actions.

Anxiety due to the apprehension of a possible wrong decision

People with a feeling of guilt often worry that they might take a wrong decision or do something they consider morally wrong. It may lead to excessive thinking and analysis of one’s actions.

Low self-esteem or, on the contrary, inflated ego

A person with a feeling of guilt may rush into extremes while evaluating himself/herself. On the one hand, he/she may have low self-esteem due to this guilt; on the other — compensate it with his/her inflated ego, trying to justify his/her actions.

Refraining from emotions

One manifestation of the feeling of guilt may be refraining from talking about one’s emotions. A person may keep his/her feelings to himself/herself, hide them from others, and sometimes even from himself/herself to avoid any confrontations and excuses.

Presence of a destructive feeling of guilt

As stated above, the feeling of guilt may be constructive, promoting the realization of mistakes and further development. On the contrary, a destructive feeling of guilt becomes an obsessive state, constantly accompanying a person. It may be related to the excessive fear of being unaccepted, the desire to feel needed, or permanent fear (e.g., “This will go on my entire life” or “This is irreparable”).

The discernment of these features and understanding of their context may be important for self-awareness and further development. If a feeling of guilt becomes a hindrance to everyday life, a person should find the assistance of a specialist who will help him/her gain insight into his/her emotions and find ways to overcome this state [9].

Why does the feeling of guilt appear?

Like many other emotions, the feeling of guilt may be studied from the psychological standpoint in the context of evolution, social factors, cognitive processes, and other aspects of psychology. Let us consider some possible reasons and explanations of why the feeling of guilt appears and how it affects our mental state:

- The evolutionary aspect: the feeling of guilt may have an evolutionary origin and be directed toward preserving the community. Such emotions as guilt may appear as a mechanism to control one’s own behaviour in a group or society, ensuring adherence to social norms and interaction in the group for the common good.

- Socialization and upbringing: since early childhood people learn social norms and values via the process of socialization and upbringing. The upbringing, which includes learning what is right and what is wrong, forms inner moral standards. We feel guilty when we break these standards or norms.

- Moral values: people have inner moral values that define what is morally right or wrong. The infringement of these values may trigger the feeling of guilt. Morality is greatly formed by cultural and social impacts and one’s personal experience.

- Self-observation: people are capable of observing their own behaviour and analysing its correspondence to moral standards. Self-observation may cause a feeling of guilt if we acknowledge that our actions are wrong or do not adhere to our own values.

- Empathy: we may feel guilty because of empathy — the ability to feel the emotions of other people. If we have become the reason for someone’s pain or troubles, empathy may enhance our feeling of guilt for the induced harm.

- Cognitive processes: internal dialogues and cognitive processes affect the formation of the feeling of guilt. For example, such inner monologues as “I have done something wrong” or “I shouldn’t have done it” may enhance the feeling of guilt.

- Self-regulation and control over one’s own actions: the feeling of guilt may appear due to one’s inability to control one’s actions or affect the consequences. It is related to the inner desire to improve oneself and avoid negative consequences of one’s actions.

- Cultural and social context: cultural and social factors have a considerable effect on how people perceive and express their feeling of guilt. The norms and values of a specific society may form and define what is considered morally acceptable or unacceptable.

- Physiological aspects: the feeling of guilt may be related to the physiological reactions of the organism, like higher stress or the activation of emotional centres in brain. The physiological processes may exacerbate or inhibit the feeling of guilt.

- Dynamics of relations: the interaction with other people and mutual relations affect the feeling of guilt. For instance, if one receives or provides support, it may change one’s perception of one’s actions and affect the feeling of guilt.

Understanding how and why the feeling of guilt appears is important for the development of strategies to manage these emotions and improve one’s mental health. Psychologists work with their clients to help them understand their own emotions, accept them, and develop constructive approaches toward managing the feeling of guilt.

The general psychological approach to understanding the feeling of guilt considers the interaction between these factors as well as the individual specificities of each person. The comprehension of the sources of this feeling and its effect helps psychologists and other specialists develop efficient methods and strategies to help people manage these emotions and improve their mental well-being [11].

Why is the feeling of guilt harmful?

Although the feeling of guilt is an essential aspect of emotional life, it may have harmful consequences, especially if it becomes too intense or lasting. Let’s consider some possible negative aspects of the feeling of guilt:

- A constant feeling of guilt may lead to psychological stress. A person may start being anxious, stressed, and lacking self-confidence, which impacts the general mental state.

- The intense feeling of guilt may affect the person’s self-esteem, which, in turn, leads to the feeling of being unnecessary and unacceptable. It may cause depression and isolation from others.

- A constant feeling of guilt may impair relations with others. A person may start avoiding any contacts, thinking that he/she does not deserve people’s support or love.

- A harmful feeling of guilt may affect the person’s physical condition. It may lead to insomnia, lack of energy, and fatigue.

- The feeling of guilt may transform into incessant self-accusation when a person constantly “punishes” himself/herself for former mistakes. Such a person may lose both faith in himself/herself and a positive attitude to life.

- The intense guilt may consume energy that could otherwise be directed toward constructive activity and self-improvement.

- A lasting emotional pressure, related to the feeling of guilt, may affect physical health, promoting the development of a disease and deterioration of the state of one’s organism.

- The feeling of guilt may affect the ability to take objective decisions. A person experiencing a deep feeling of guilt may be inclined to exaggerate the negative consequences of one’s actions and take wrong decisions aimed at self-punishment.

- A constant guilt may deprive a person of any joy in life. A person may feel unworthy of joy and pleasures, which leads to a general decrease in life quality.

People with a constant feeling of guilt may avoid meetings with others and isolate themselves. Their fear of not being accepted by others and lack of self-confidence may become the reason for their refusal to engage in social interactions.

The feeling of guilt may lead to a refusal to pursue personal goals and ambitions. People may believe that they do not deserve any success or a happy life because of the mistakes they have made.

An exaggerated feeling of guilt may lead to the loss of self-confidence. A person may be sure that he/she constantly makes mistakes and can’t change his/her situation, which may lead to hopelessness and loss of motivation.

The feeling of guilt may cover the entire family or relations. A person may affect the moods and emotions of other family members, creating pressure or a negative environment.

To cope with the feeling of guilt effectively, it is important to develop the strategies of self-management of emotions, to view the mistakes that were made as a possibility for further improvement. Psychological support and conversations with professionals may also be useful to overcome the negative consequences of the feeling of guilt [6].

How does one get rid of the feeling of guilt?

Getting rid of guilt is a complicated process, which requires self-reflection, understanding the reasons for these emotions, and determination to find constructive ways of overcoming them. Here are some strategies to help you manage and reduce the feeling of guilt:

Self-analysis and awareness

- Realize the reason for the feeling of guilt: try to find out why exactly you feel guilty. Was it an actual mistake or exaggerated self-criticism? Your understanding of the reasons may help you determine whether there are any grounds for the feeling of guilt.

- Evaluate the scope of the mistake: think about the scope and severity of the error or action which triggered the feeling of guilt. Sometimes, it may turn out that self-accusation is exaggerated, and you should accept yourself and work on your emotional state instead of focusing on guilt or shame.

Taking responsibility and correcting mistakes

- Take responsibility for your actions: if the guilt is based on actual mistakes, it is important to accept responsibility for your actions. Acknowledgement of mistakes is the first step toward rectifying the situation.

- Act constructively: instead of self-accusations, concentrate on how you can rectify the situation. Act constructively, looking for ways to improve and correct the mistakes.

Building your self-esteem

- Work on your self-esteem: develop a realistic and positive self-perception. Remember that we all make mistakes, and they are a part of our lives.

Communicating with others

- Share your feelings: discussing your feelings with trusted friends, relatives, or a professional psychologist may be useful. Others can give you an objective perspective of the situation and help you find ways to overcome your feelings.

- Accept support: ask for help when you need it. Others can give you compassion, commiseration, and advice.

Practicing meditation

- Concentrate on the current moment: meditation can help you concentrate your attention on the current moment, reduce your stress, and mitigate your experience of these emotions.

- Practice breathing exercises: a deep and conscientious breathing process can calm the nervous system down and reduce emotional stress.

Developing the strategies of self-regulation of emotions

- Study the relaxation techniques: Such relaxation techniques as deep breathing, yoga, or walks in the open air can promote a decrease in the level of stress and emotional tension.

- Use positive affirmations: affirmations, also called positive statements, are phrases, regular repetition of which can change negative thoughts and behavioural models. They can be pronounced out loud or inwardly. Usually, the purpose of these statements is to help switch your thinking from negative to positive, motivate you to actions, decrease stress, help you survive in difficult times, and improve your self-confidence and well-being. Positive affirmations can help change your negative inner dialogue and promote the improvement in your self-perception.

Letting go of perfectionism

- Accept yourself: realize that nobody is ideal, and failures are an integral part of life. Accept yourself together with your strengths and possibilities for growth.

- Concentrate on the process instead of the result: try to evaluate your actions and achievements not only by results but by the process itself as well.

Doing good to others

- Volunteer and help others: your own contribution to good deeds and helping others can help you balance the feeling of guilt, promoting the creation of a positive contribution to this world.

- Forgive yourself and learn to forgive others: forgiving is a relevant step in the process of solving conflicts and reducing the feeling of guilt. If possible, forgive yourself for your mistakes and learn to forgive others.

Working with a professional psychologist

- Therapy: the sessions of individual or group therapy may be effective for the understanding of the roots of the feeling of guilt and the elaboration of the strategies of its management.

Remember that the feeling of guilt is a normal emotion, but it is important to find healthy and constructive ways to manage it. If you feel that you can’t cope with the feeling of guilt on your own, you should ask a specialist, for instance, a psychologist, for help [13].

Remember that the process of getting rid of the feeling of guilt is an individual path, and you might need time to achieve positive results. If you feel that you can’t cope with the feeling of guilt on your own, a visit to the specialist may be an important step on the path to psychological well-being.

Techniques

-

- The exercise “My “guilty” thoughts” (S. Bronnikova)

The instruction:

Recollect the situation — a current one, the one from the past, from your childhood, which triggered a long-lasting feeling in you. Write down a short account of what happened on that occasion. Recollect your feelings about that story, spend some time, and allow yourself to dive into experiencing this guilt. When it overwhelms you, think of the only reason — just any reason – which will let you feel not that guilty.

- Maybe you have already been forgiven for what you did? Or perhaps you have taken some steps to rectify the situation?

- Any reason will do!

Now that you have managed to think of one reason, contrive two more. You have forbidden yourself to forgive your very self for a long time, naming possible reasons not to feel so much guilt to be mere subterfuges and excuses; you have actually been using your own “inner prosecutor”, a merciless accuser. It is time to give the floor to the “inner attorney” as well.

Has it worked out? Now that you have three reasons not to feel so guilty, contrive the last, fourth reason not to feel any guilt for this story at all.

- Have you managed to reduce your feeling of guilt? How do you perceive it?

- Note how rational thinking allows you to overcome your guilt. Let yourself forgive.

-

- The exercise “A Counter of Guilty Thoughts” (S. Bronnikova)

The instruction:

Imagine always carrying a counter of guilt, which scrupulously registers each time you experience this feeling.

How many times have you felt guilty today? What about yesterday? And last week? Try to recollect and analyse each time.

Evaluate how adequate and deserved each of these feelings was (each and every time!).

Describe each time in short.

What have you noted after this exercise?

Did you discover anything new after doing it?

Guilt may form a habit just like any other emotion. Don’t yield to your usual guilt and reflect on it each time it appears in your mind.

-

- The exercise “A Daily Mood Log, Automatic Thoughts” (David Burns)

The instruction:

A person is suggested to fill in the table.

Describe the event triggering your feeling of guilt in column “Situation” (see Table 2).

Table 2. Registration of automatic thoughts

|

Situation |

Emotions |

Thoughts, triggering the feeling of guilt |

Cognitive distortions |

Rational response |

Result |

Then, “tune in” to the tyrant’s voice in your head and write down specific accusations that cause your feeling of guilt.

Analyse these accusations and find cognitive distortions. Write down the most objective thoughts regarding these cognitive distortions.

As a result, you will feel relieved.

1. The Exercise “Transformation of the Negative Mindset into the Positive One”

The instruction:

І. Draw a table with the following columns:

- an upsetting situation;

- negative thoughts/mindsets you have had after this situation;

- your emotion after these thoughts;

- your behaviour after this emotion.

ІІ. Fill in Table 3.

Table 3. Registration and analysis of negative thoughts/mindsets, emotions, and behaviour after a specific situation

|

Upsetting situation |

Negative thoughts/mindsets you have had after this situation |

Your emotion after these thoughts |

Your behaviour after this emotion |

ІІІ. Imagine that you are a non-judgemental adult, looking at this table from aside, and analyse each thought/mindset you have written (the second column in Table 3).

ІV. Draw the following table and break it into arguments that support this thought or refute it (see Table 4).

Table 4.

Registration of arguments that support a specific thought

or refute it

|

Negative thoughts/mindsets you have had after this situation |

Arguments, supporting this thought |

Arguments, refuting this thought |

- Fill in Table 4 as honestly as possible, reviewing each thought/mindset that you have written in the first table.

VІ. Transform each negative thought/mindset into a positive one (fill in the third column of Table 4). The main thing to be considered while transforming a thought/mindset is that a positive formulation should be written in the Present tense as an urge to act. It means that you should not write the opposite meaning of the mindset (e.g., I am not successful — I am successful); instead, you should write the explanations for the negative mindset and the ways of achieving this positive mindset.

So, we have described the essence of some exercises and methods of working with the feeling of guilt. However, each case of a client experiencing the feeling of guilt is unique because it has different reasons, a different degree and depth of this feeling, and, thus, requires an individual approach.

The material was elaborated and formed by:

Oleksandr Hapon (Chernihiv)

References:

-

- Baumeister, RF, Stillwell, AM, & Heatherton, TF (1994). Guilt: An interpersonal approach. Psychological Bulletin, 115, 243–267.

- Dilts, R. (1990). Changing beliefs with nlp. Capitola, CA: Meta. 1990.

- Belik I.A. A feeling of guilt due to the specificities in the development of a personality: A Ph.D. thesis. SPb., 2006. [In Russian]

- Vasiliuk F.E. Psychology of Experience. M., MGU. 1984. 198 p. [in Russian]

- David Westbrook D., Kennerley H., Kirk J. An Introduction to Cognitive Behaviour Therapy. Lviv: Svichado, 2014. 420 p. [in Ukrainian]

- Il’in E.P. Psychology of Conscience: guilt, shame, remorse. — SPb: Piter, 2016. 288 p. [in Russian]

- Klein M. On the theory of guilt and anxiety. Translated from Eng. by D.V. Poltavets, S.G. Duras, I.A. Perelygin / Development in psychoanalysis. Comp. and scient. ed. I.Yu. Romanov. – M.: Akademicheskiy proekt, 2001. – 512 p. – P. 394–423. [In Russian]

- Kornilov M. N. “Culture of shame” and “culture of guilt” in Japan and the West. A human being: image and essence. M., 1998. Iss. 9. P. 94-112. [In Russian]

- Maleeva O.L. Genesis and functions of guilt / O.L. Maleeva // Scientific bulletin of PDPU n.a. К. D. Ushynskyi, 2007. No. 7–8. P. 247–256 [in Ukrainian]

- Matlasevych O.V. Feeling of guilt in psychological and religious interpretation. Scientific notes. Psychology and pedagogics series, 2011. Iss. 17. P. 231-241. [In Ukrainian]

- Tsarkova O.V. The feeling of guilt and its visualization in archetypal symbolism / O.V. Tsarkova // Pedagogics and psychology: current problems and development prospects: Materials of the international scientific and practical conference (Kyiv, Ukraine, November 3, 2012). – Kyiv: NGO “Kyiv Scientific Organization for Pedagogics and Psychology”, 2012. – P. 117–119. [In Ukrainian]

- Tsarkova O.V. The feeling of guilt as one of the aspects in the development of a personality and his/her social interaction / O.V. Tsarkova // Scientific bulletin of the Kherson State University. Psychological sciences series: a collection of scientific publications. — 2014. – V. 2, Iss. 1. – P. 79–84. [In Ukrainian]

- Tsarkova O.V. Psychological phenomenon of guilt in the secular and spiritual ethics / O.V. Tsarkova // Materials of the All-Ukrainian Scientific and Practical Conference. Christian ethics in the history of Ukraine and a modern dialogue of outlook and spiritual identities (November 27–28, 2014), Melitopol, Ukraine, 2014. — Melitopol. – P. 123–130. [In Ukrainian]

- Tsarkova O.V. Psychology of guilt experience in parents of children with psychophysical developmental abnormalities: a monograph / O.V. Tsarkova. Kyiv: Interservice. 2016. – 256 p. [in Ukrainian]

- Tsarkova O.V. A phenomenon of the feeling of guilt in the context of psychoanalytical approach / O.V. Tsarkova // Path of Science. International scientific journal, 2015. No. 8 (18) – 2015. – P. 87-89. [in Ukrainian]

Stress

We often hear the word “stress” in our daily life; moreover, we experience stressful situations almost daily. Stress has different kinds of impact on our organism. In some situations, it is a factor needed for survival, a motivator, urging to action. In others, it impairs the entire work of the organism, causing psychosomatic diseases. Hans Selye stated that stress is a non-specific reaction of the organism to the exaggerated requirement to it [5].

Stress can be biological and psychological. To differentiate between the types of stress, answer this question, “Does stress have a direct impact on my organism?” If your answer is “Yes”, then it is a biological stress; if the answer is “No” — it is psychological.

The objective reasons for the stresses of a contemporary person may be combined into four groups:

- conditions of life and work (living conditions, industrial factors, ecology);

- people he/she interacts with (a demanding boss, bad neighbours, careless subordinates);

- social environment factors — political and economic factors (high prices, loan terms, bad authorities, taxes);

- emergencies (war, natural and technogenic catastrophes, diseases, and traumas).

In his theory, H. Selye also suggested the structure of stress, which, in his opinion, consists of specific stages. A stress has a different course depending on the stage.

1. The stage of alarm, also called “fight / flight / freeze”: at this moment, the organism is experiencing a release of hormones which adjust it to the stressful conditions as fast as possible.

2. The stage of permanent (chronic) stress: the experience of chronic stress is accompanied by hypertension (strong tension) or hypotension (relaxation) of muscles, which changes posture and walking.

3. The last stage — exhaustion: the symptoms manifesting that a person is in this stage are slow speech, confused thinking, helplessness, weakness, and apathy.

Stress affects people’s emotions, mood, and behaviour. Its impact on a human organism is relevant indeed and sometimes even very serious.

Negative consequences of stress: bouts of aggression, rage, irritability; mood swings; loss of energy and interest in life; impaired concentration, understanding, and ability to learn, memorize, and express one’s thoughts; sleep disorders; constant headaches; loss of self-confidence, neurosis; heart rhythm disorder; acute exacerbation of chronic diseases; hormonal disorders; impaired productivity; increased risk of cancer; constantly depressed emotional state.

This list of consequences demonstrates that under stress, the physiology and emotions of a person are closely interrelated in a highly complicated system. This is an enormous effect of emotions, experienced by a person under stress, on the work and state of almost every cell in a human body. Scientific publications show that a person can conscientiously use this association between the mind and body to eliminate the emotional and physical harm, done by the stress.

It is common knowledge that yogis have marvellous abilities to manage their bodies and physiological functions. The research has proved that not only yogis, but also common people can learn how to manage their heart rate, muscle relaxation, work of sweat glands, body temperature, and other physiological reactions of people to stress.

The first step to minimizing the harmful effects of stress can be the realization of individual physiological responses to stress.

For instance, while experiencing stress, a person starts taking frequent fast breaths, which is a reaction of the human body to such negative emotions as strong fear, sorrow, despondence, or a feeling of utter hopelessness of one’s fate. Rapid breathing is a consequence of accelerated heart work, which may lead to higher blood pressure and other negative consequences. Therefore, the stabilization of breathing is granted a relevant place in the strategies of dealing with stress, which suggest so-called “breathing” exercises, Chi Kung, borrowed from Chinese medicine. This term is used to denote different types of relative psychophysiological energy, such as the air we breathe in. Having some control over breathing, a person can affect the work of the internal organs, including the cardiovascular system. Below is one of the basic exercises that will help you not only normalize the work of your heart but also decrease the level of stress hormones, increase your concentration, and improve your sleep:

- Relax your body (try to shake your arms and legs, massage your shoulders, etc.).

- Imagine that you have a balloon in your stomach, and your task is to fill it with air.

- Put one hand on your belly and another one – on your chest; it may help you make sure that you are breathing with your belly, not with your chest.

- Take a deep and slow breath with your nose. Your belly will get inflated. Try not to breathe with your chest.

- While breathing in, count 1, 2, 3 (in seconds).

- Exhale through your mouth as slowly as possible. Count 1, 2, 3 (in seconds) while breathing out to feel your lungs getting rid of air.

- Do this exercise for at least two minutes, counting aloud. You can also count in silence or listen to the clock ticking or any other rhythm.

The advantages of this breathing exercise can be felt even when you do it for the first time. It takes about ten to twelve minutes for tense shoulders to relax, for the heartbeat to slow down, and for the flush of anxious thoughts to calm down.

Stress can also cause the contraction of your body muscles. For example, fear is accompanied by a spasm of muscles, responsible for speech. Muscle tension can also lead to tremor, uncontrolled movements, and woodiness. These may be relieved using the method of progressive muscle relaxation of E. Jacobson — an intended relaxation of muscles accompanied by a decrease in nervous and muscular tension.

All the muscles in the body can be divided into the following groups: arm muscles, leg muscles, torso muscles, neck muscles, and facial muscles. Each “contraction-relaxation” cycle for each group of muscles takes about one minute and is repeated 3–5 times. Muscles are flexed while holding breath for 15–20 seconds after inhaling and relaxed while exhaling. The exercises should be done stepwise. Move on to the next exercise only after the previous one has been learned.

- PALMS: put your hands on the table (clench your fists as hard as possible, as if you are squeezing water from an icicle).

- FEET: bring the tops of your feet back toward your knees with your toes clenched.

- CALVES-THIGHS: straighten your toes, raise your heels.

- CHEST-BACK: try to put your shoulder blades together.

- SHOULDERS: reach your ears with your shoulders.

- UPPER THIRD OF THE FACE: wrinkle your forehead (make a surprised face).

- MIDDLE THIRD OF THE FACE: add a cross-eyed expression to the wrinkled forehead.

- LOWER THIRD OF THE FACE: “Pinocchio” (pull your mouth corners to your ears), “Kiss”.

Arbitrarily relieving the tension of a specific group of muscles, you can manage your negative emotions and calm down.

If you don’t work on muscle tension induced by stress, the woodiness of your body may become chronic, which damages emotional health by reducing your individual energy and limiting your mobility. Body-oriented techniques are also the ways to manage the bioenergy of the organism, help it release and get rid of body tension. Below is a classic technique that helps feel the areas of tension in the body and get rid of them.

“Lowen’s Ring”: Put your feet 25 cm apart, slightly turn your toes inward and bend forward with your waist. Bend your knees and touch the floor with your fingers. Transfer the weight of your body to your toes. Take deep breaths with your mouth. Slowly straighten your knees. Hold still for about a minute. Your legs will start trembling. Trembling is a natural reaction of your body to tension and is an indicator of the energization of your tense muscles. The Ring exercise is done to enhance the feeling of “the foundation under your feet”, i.e., the contact between your feet and the ground. When you are finishing the exercise, you should straighten yourself very slowly.

It has already been stated that under stress, a person produces both physiological and emotional reactions. One of these reactions may be aggression. It triggers many conflicts during a war, which is a severe, stressful situation for people. Therefore, it is reasonable to often use constructive strategies of combating one’s stress and discharging the aggression.

For this purpose, a body-oriented exercise is suggested, which is called “A Discharge of Rage”: stand up facing the object (a bed, an armchair, a large pillow), keeping your feet 45 cm apart, slightly bending your knees, and lay blows (using a plastic beater, a tennis rocket, or your own fists) on this object in a strong but relaxed manner. Engage your entire body in this action. Keep your mouth open, take deep breaths, and do not restrain your shouting. You can use any words to express your feeling of rage.

The suggested techniques are basic but not exhaustive ways of working with the psychophysiological level of stress regulation. To help yourself manage your stress and decrease its effect on your life, you can change your behaviour and form new habits:

- Stay physically active.

- Have a balanced diet.

- Minimize your use of gadgets and reduce your screen time.

- Allocate some time for planning.

- Set some boundaries and learn to say “no”.

- Take care of yourself!

The material was elaborated and formed by: Lesia Kovpaka, Veronika Myshkivska (Zhytomyr).

References:

- The World Health Organization. Problem Management Plus (PM+): A textbook on holding a training for PM+ consultants. Geneva, WHO, 2018.

- James S. Gordon. Transforming Trauma / transl. from English by Halyna Stashkiv. – Lviv: Litopys, 2023. – 352 p. [in Ukrainian]

- Rozov V.І. Adaptive anti-stress psychotechnologies: A textbook. – K.: Kondor, 2005. – 278 p. [in Ukrainian]

- Sapolsky Robert M. Why zebras don’t get ulcers / transl. from English by O. Lobastova. – Kharkiv: Ranok Publishing House: Fabula, 2020. – 400 p. [in Ukrainian]

- Selye H. Stress without distress. / Hans Selye; translated from Eng. / [Electronic resource]. – URL-access: http://bookz.ru/authors/sel_e-gans/distree/page-2-distree.html

Anxiety

Anxiety is an unpleasant emotional state characterized by the expectation of an unfavourable course of events, the presence of foreboding, fear, tension, and worry.

Anxiousness is an individual psychological specificity manifested in an inclination to often feel strong anxiety regarding insignificant factors. It is considered to be either a personal feature or a temperament trait related to weak nervous processes, or both at the same time.

This state is necessary for

- signalling about danger. It is required for survival.

- mobilizing inner resources. It happens without conscientious efforts — a body already knows what to do in dangerous situations.

We are born with different levels of anxiousness, and an inclination for anxiety is genetically predetermined.

Some people worry less because their nervous system is composed of slightly thicker nervous fibres. It takes more time for the impulse to go along that fibre, so people are calmer. The parts of the brain, responsible for the perception of anxious impulses, work in a more relaxed mode.

Some people have a very sensitive nervous system and react to triggers very fast. The system of reacting to a threat is also more sensitive, and it does not depend on our wilful efforts.

The level of anxiety is also affected by such psychological factors as stressful situations in one’s childhood, self-esteem, life experience, etc. Genetics, combined with our life experience, makes each of us a person with a specific level of anxiousness, different from others [1].

There are some myths about anxiety...

Strong anxiety is abnormal X

Fear or strong anxiety is a normal reaction of adapting or reacting to the immediate danger, conflict, or stress √

Only weak people can have anxiety X

Anxiety is a natural feeling, inherent to absolutely everyone √

Very often, bad thoughts “persecute” us because of idleness, so any work is wonderful therapy for an anxious state. When a person is engaged in active physical or mental activity, all the worries are left aside, one simply does not have time for them √

Some people believe that anxiety is a part of their personality, so there is nothing to be done; there can be no therapy or treatment that could improve it X

The manifestations of anxiousness [2]

|

Emotional features |

Behavioural features |

Physiological features |

|

- Permanent feeling of danger, fear - Problems with attention concentration - Unrest, impatience - Pessimism - Irritability - Search for the signs of danger - Devastation |

- Inability to relax, enjoy some rest, be oneself - Difficulties with concentration - Procrastination, delaying tasks - Loss of trust in life and people - Avoiding the situations that may evoke anxiety |

- Muscle tension - Pain in the body - Cold sweat - Accelerated heartbeat, trembling, shortness of breath - Sleep problems - Problems with stomach, nausea, diarrhoea - Sharp fluctuations in appetite Mental tension |

Fig. 1. The manifestations of anxiousness

When anxiety is felt on the level of emotions

During a bout of anxiety, the heart and respiratory rates are accelerated, and a person may be sweating excessively or even feel dizzy. In such moments, controlled breathing may help relax both the body and the mind. To take control over the breathing process during a bout of anxiety, one should take the following actions: sit down in a quiet place. Put one hand on the chest and another one — on the belly. When taking deep breaths, the belly should move more than the chest. Take a slow breath through the nose and exhale through the mouth. Repeat the exercise at least ten times or until feeling that anxiety is receding.

On the level of behaviour, it is necessary:

- To allocate some time for anxiety and to define the amount of this time (for instance, twice a week, from 6 p.m. till 7 p.m., I allow myself manifest and feel my anxiety and my anxious thoughts).

- To start doing small good deeds. Think whom you can help and in what way.

- To make up a list of deeds. Routine.

We suggest the following exercises for a high level of anxiety. Exercise 1.

1. Write down the situation that has triggered your worry.

2. Then divide a piece of paper into four parts.

Part one — the situation. Here, you write down everything that is going on globally, which is neither good nor bad for the world. This is a “cold reality”. Events happen in the world just because they do.

Part two — the thoughts about the situations, involving you personally or happening around you. People attribute specific meaning to some situations, which makes them personal.

Part three — emotions: what you think you will feel regarding this situation. But the situation remains unchanged.

Part four — behaviour: emotions force people to engage in some behaviour (fight, flight, freeze).

- Analyse what you have written. Answer the following questions:

— Which part has been filled the most?

— Which part has been filled the least, or has nothing written on it at all?

— Which conclusions can I now draw about my situation?

This exercise helps a person see and understand which aspect he/she focuses his/her attention on (the part which was filled the most). For instance, if these are merely thoughts, and nothing is written in the part for actions, it demonstrates that a person worries only about the thoughts, so they should be “converted”, transformed into actions; a person must start doing something, find a structure for this situation by dividing thoughts, emotions, and behaviour apart.

Exercise 2. If you constantly have too many thoughts, start keeping a diary of anxious thoughts.

- Every morning, write down all your anxious thoughts as of that moment. What for?

- When a person writes something down, he/she takes it out of his/her head, actually distances himself/herself from these thoughts.

- When a person has anxious thoughts, it seems that his/her mind is in chaos. When a person writes them down, it may turn out that they are not that numerous.

- The changes in these thoughts and their transformation can be traced.

Keeping a diary is a universal method of coping with a stressful situation. It helps comprehend and transform all the chaos in one’s mind.

- After that, all the written anxious thoughts should be evaluated (e.g., on a scale from 1 to 5, where everything below three should not cause anxiety, so you are not wasting your time on that), or assessed in % to see how much you believe in this thought, and if the percentage is high — write down a list of arguments, proving that it is actually so, then this anxiety is helpful, and you should make a plan.

- Evaluate the usefulness/uselessness of your anxiety

It is useful when a person can do something to change the situation. Then, this anxiety will help brace oneself, mobilize strength, and take some measures, e.g., to protect oneself from danger. On the contrary, anxiety is useless when people understand that they have done everything they could in this situation but still worry very much and can do nothing with themselves.

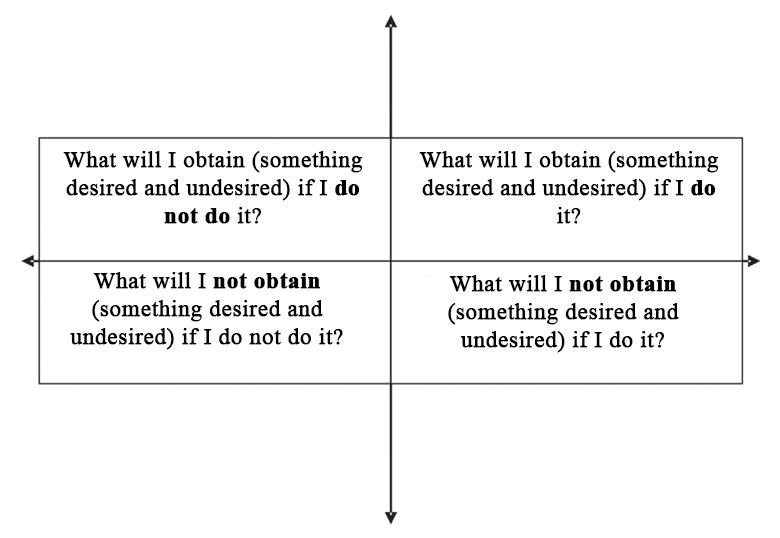

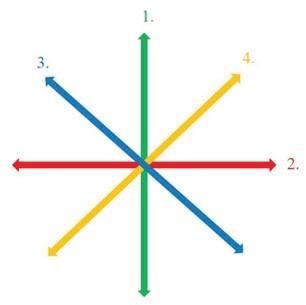

Exercise 3. Coaching technique “Descartes’ Coordinates”

Our psyche perceives changes easier when we are ready for them, have visualized or written down the plan of changes, and enlisted the support of others, who are significant to us or are not indifferent to us.

Fig. 2. A scheme for the coaching technique “Descartes’ Coordinates”

The essence of the technique is to expand the vision for possible prospects. This technique works on the level of abilities and possibilities and is used in coaching on the stage of clarifying the reality.

A step-by-step description of the technique “Descartes’ Coordinates”

Choose any event or action that may happen or that you are about to take, but you are still hesitant.

Example. “I am going to find a new job.”

Fill in all four quadrants, presented above (also called “Cartesian quadrants”), and write down 6–10 answers to each of the questions. Avoid copying the answers; don’t transfer them blindly from one column to another; answer each question separately. Despite some similarities between questions, they highlight different focuses of attention, and the answers will be different. Some answers may be repeated, but the greater difference you have in the perspective, the better.

How has your idea about your goal expanded? First of all, ask yourself whether you consent to the losses that you might suffer by achieving your goal. If not, think about the ways to achieve your goal and avoid these losses. Find these ways.

What about your motivation? If it is still insufficient, concentrate for a few minutes and think sensibly and in detail about the pluses you will receive due to achieving this goal and about the minuses you might get rid of.

Note important results that you obtained from your work and adjust them for the future. Where, when, and how will you start achieving your own goal? Range your answers in the order of descending significance.

The material was elaborated and formed by:

Olha Uhryn, Natalia Vasylets, Serhii Tkachuk (Lviv)

References:

- Stanchyshyn V. Walls in my head. Living with anxiety and depression. К.: Vihola, 2020. 175 p. [in Ukrainian]

- Anxiousness. URL-access: https://healthcenter.od.ua/ psyhichne-zdorovya/tryvozhnist/

- Krachun K. Life in one suitcase. – K.: Psychobook, a publishing house of psychological literature, 2023. 178 p. [in Ukrainian]

Take a test to determine your level of anxiety.

Scan the code.

Fear

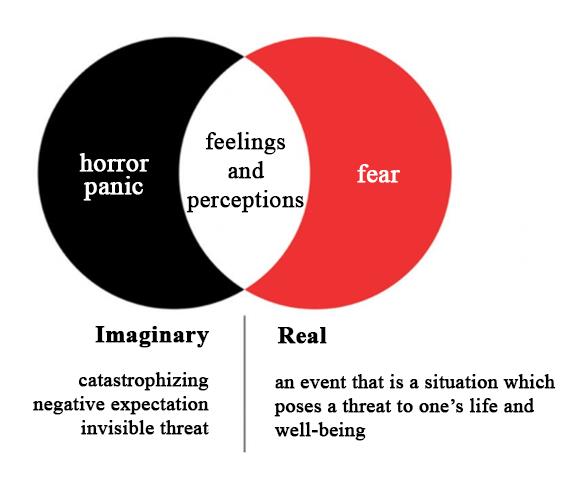

In modern psychology, fear is considered to be a deep basic emotion, which is manifested as a reaction to a relevant situation.

As per the definition in the reference book of psychological terms:

Fear is an inner emotional state which a person has when facing an imaginary or actual threat to his/her life or well-being. Depending on the situation, the degree of the danger from it, and the individual specificities of a person, it may be of different intensity: from being a bit apprehensive of terror to complete paralysis of movements and speech.

If the source of danger is not defined or poorly comprehended, a person will have anxiety. When fear comes, a person feels uncertainty, unrest, insecurity, and a threat. The fundamental trait of fear is to warn a person about a possible danger, which helps him/her concentrate and avoid it. The emotion of fear may be either exciting or inhibiting and induce different reactions in people: a panicky flight, defensive aggression, or complete freezing.

The emotional mask of fear on a face is created by horizontal wrinkles on the forehead, wide-open eyes, and tense lips (sometimes an open mouth) [1].

Fig. 1. A graphic representation of determining a threat

Thus, fear is a normal reaction of a person to a threatening situation which fulfils the protective function. Abnormal fear (not fulfilling the protective function) is the fear that occurs without any objective reason or lasts for a very long time (over two weeks after the situation). This fear is called a phobia, and it requires the assistance of a specialist. It should also be noted that the most substantial fear for people is the possibility of violence toward them personally. It means that the threat of violence will always give rise to a reaction of fear [2].

One of the specificities of fear is its possible transmission from one person to another. If you are in an environment governed by fear, after a certain period, you will also come under its influence. The higher the number of people who suffer from fear and panic is, the more intense the feeling of fear is.

Fear also has its common bodily reactions, notable for all people:

- tremor in limbs;

- stomach spasms with possible diarrhoea;

- more frequent urges to visit the bathroom;

- muscular tension in the entire body or some parts of the body;

- nausea, vomiting;

- impossibility of staying in one place;

- sleepiness, tiredness;

- woody movements, clumsiness;

- pale or, on the contrary, red skin;

- dilatation of pupils.

It should be noted that these reactions are normal; they are common for most people, experiencing fear.

How do we react?

An immediate threat — a reaction — selecting a strategy — an action.

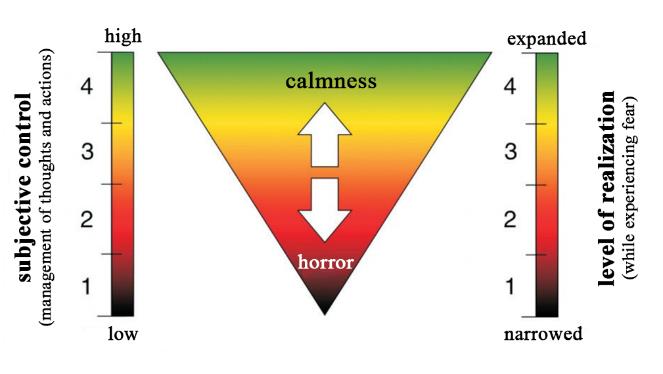

The regularity is: the more potent the effect of fear is, the lower the level of subjective control is. As per the definition by Julian Rotter, the level of subjective control (LSC) is the ability of a person to control himself/herself and his/her behaviour, to manage it, and to take responsibility for the things happening to and around him/her.

This scheme is the interpretation of theories, demonstrating the scale of experiencing fear. The higher the level of fear is, the lower control is, and vice versa [3].

The level of subjective control

Fig. 2. A graphic representation of the level of subjective control

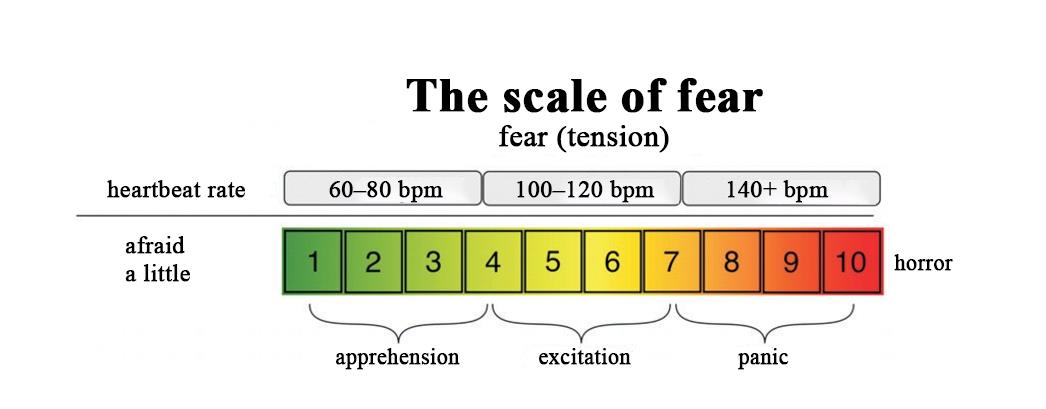

It is important to define the level of fear and choose the relevant techniques and exercises based on it.

Fig. 3. The scale of fear

1–4 — apprehension — in this range, a person can plan and act despite the feeling of fear;

4–7 — excitation — in this range, a person is worried about a somewhat reduced ability to act;

7–10 — panic — in this state, a person has a poorer ability to think rationally and control one’s actions.

Self-regulation can be achieved using four main methods separately or in different combinations: the effect of a word, a made-up image, management of muscle tone, and deep breathing.

The exercises and techniques below are suggested for different levels of fear and different situations, starting with more severe feelings.

8–10

6–8

4–7

3–5

1–4

How to act in a complicated situation when there is nobody around?

Helping a person nearby.

A technique of progressive relaxation, suggested by Edmund Jacobson

The exercise “Gaining More Self-Confidence”

A technique of reducing fear to an absurdity

A method “Fortress”

8-10

If you have found yourself in a situation where you feel overwhelmed by fear, it may be difficult to find your bearing and understand what you should do. You may feel like you are not present in your own body, like the ground crumbles under your feet. So, what should you do in this case?

- Start stamping your feet with great force. It will help you feel the ground under your feet and return to your body.

- After returning to your body, flex it: your arms, legs, and trunk. You can tap along your entire body, starting with the upper part and going down.

- Add breathing: take a deep breath — exhale deeply. If you can count, inhale while counting to 4, and breathe out while counting to 5. Then, take a breath while counting to 5, and exhale while counting to 6. Gradually add the depth of your breathing.

- Look at your environment: find five objects, for instance, “I see a chair; it is brown.” “I see a vase of green colour, I see the door of grey colour, I see four people, they are dressed in (describe the items of clothing).” It is required to bring your conscience back to the current moment, to relieve the tension, and to decrease the level of fear. You should come back to the moment, place, and space you are in. Then, you can react to the situation itself in a more objective way. When the danger has passed, tap along your body once again to relieve the additional tension.

8-10

If you are close to a person who is deeply frightened and cannot control his/her actions, it is reasonable to use the protocol of providing psychological first aid in stressful situations while helping him/her (O. Gershanov).

- You should calm yourself down first and be in a rather stable emotional state. You are going to help someone in the same stressful situation — and you actually have the same emotions. Your difference should be based on the fact that your anxiety will be reduced sooner because you can control your emotions.

- It is very important not to talk about emotions. In such situations, you should “switch on” other zones of your brain.

- You should not say things like, “Calm down. Everything will be fine. Things will get better”, etc., because such phrases will only add to the feeling of loneliness in this situation. A person will feel that you don’t understand him/her even if he/she asserts the opposite.

- You should slow yourself down to slow down the reactions of the person you are trying to help. You should speak more slowly than usual. Why? It is required for us to become more real to a person and to give him/her a feeling of support, confidence, and stability because the external world of the person we are helping has been shattered.

- Talk in clear, short phrases. You can even raise your voice a bit. You can start with the phrase, “Look at me.” At this moment, a person sees everything with a narrowed tunnel vision. So, your task is to expand this tunnel.

- You should make contact and give the first feeling of something else present here, except the horror a person has experienced. First, say your name. It is better not to use the terms like “psychologist”, “psychiatrist”, “psychotherapist” — a person may start worrying additionally that something is wrong with him/her.

- Ask this person, “What is your name?”

- Then, ask him/her where he/she was going, what he/she was doing, what he/she was going to do when... (the siren went on, the shelling started — name the situation). Severe stress may shatter life continuity. These questions unite the events into one whole, bringing back the feeling of continuous life.

- Repeat a person’s answer after him/her clearly and comprehensively. Add if you know the situation. No emotions and details. State the sequence of events before the stressful event, the event itself, and what happened after it.

- You should help a person recover his/her feeling of control and his/her own significance. For instance, you can count people around you, look at the numbers of houses, etc.

- Normalization. Say, “All your feelings (list everything you see, for example, fear, tears, stupor, confusion, panic, anxiety, etc.) are a normal reaction to an abnormal situation.”

- A search for resources. Your goal is to end the conversation with a person on the topic of resources. It is important for a person to recollect his/her own examples and variants of coping with a stressful situation. Any instruments of coping — having a walk, running, food, etc. (any variants except alcohol and drugs) are acceptable. Our task is not to evaluate the ways of overcoming stress. The best way to survive in shocking, stressful situations is to restore your control (by actions) and relations with other people.

Sometimes, a person may have a mental block and fail to react to your voice. Try to speak louder and with confidence, and use some visual factors (e.g., wave your hand in front of his/her eyes). However, do not engage in physical contact; do not physically touch a person because you don’t know what reaction he/she might have. You can give him/her something with contrastive characteristics to hold (e.g., a very cold object.).

Let a person speak out. Do not start a discussion with him/her, do not contradict, do not persuade him/her of anything. By doing so, you will let a person feel noticeable and understood in this situation. Every word can either support or traumatize. So, don’t argue with the person you are now trying to help. Speak in simple words and do not use complicated words or terms [4].

6-8

Tension in your body is a consequence of fear, stress, and anxiety. Being under stress and anxiety, your brain sends your body some signals that require constant readiness to react to danger. It leads to your feeling of muscular tension and the impossibility of relaxing. The technique of progressive muscular relaxation is aimed at decreasing the physical tension and achieving relaxation. Its main essence is as follows: alternation between contraction/relaxation of different groups of muscles in a specific sequence.

Find a quiet place, lie on the floor or tip back in your chair, put your hands on your knees. Take a few slow and steady breaths.

Now, focus your attention on the following zones, trying to keep the rest of your body relaxed.

Forehead. Wrinkle your forehead for 15 seconds. Feel your muscles getting tense. Now, slowly relax your forehead, counting to 30. Pay attention to the difference in the muscular feelings when you relax. Breathe slowly and steadily.

Jaws. Contract the muscles of your jaws for 15 seconds. Now, slowly relieve the tension, counting to 30. Pay attention to the feeling of relaxation and keep breathing slowly and steadily.

Neck and shoulders. Increase the tension in your neck and shoulders by raising your shoulders to your ears and keeping this posture for 15 seconds. Slowly relieve the tension, counting to 30. Pay attention to the tension leaving you.

Arms and hands. Slowly clench your both hands into fists. Press them to your chest and stay in this position for 15 seconds, clenching them as hard as possible. Now, slowly relax them, counting to 30. Pay attention to the feeling of relaxation.

Buttocks. Slowly increase the tension in your buttocks for 15 seconds. Now, slowly relieve the tension for 30 seconds. Pay attention to the tension leaving you.

Legs. Slowly increase the tension in your legs for 15 seconds. Flex your muscles as hard as you can. Now, slowly relieve the tension for 30 seconds. Pay attention to the tension leaving you and the feeling of relaxation remaining with you.

Feet. Slowly increase the tension in your feet and toes. Contract your muscles as much as you can. Now, slowly relieve the tension, counting to 30. Note how all the tension is disappearing.

Enjoy the feeling of relaxation streaming in your body. Continue breathing slowly and steadily.

Recommendations for the technique:

Give yourself 15–20 minutes for this technique at the same time each day, e.g., before going to sleep. Do it in a quiet and comfortable place.

Turn off your phone to avoid distractions. Try not to hold your breath — it may increase the tension. Take a deep breath when you contract muscles, and exhale completely when you relax.

Do the exercise in the order that suits you best. For example, you may start with your head and move downwards or vice versa.